NASA’s New Horizons successfully reaches Ultima Thule

New Horizons is the spacecraft which took some spectacular photographs of Pluto back in 2015. It was no surprise that Pluto was found to be a very cold world. What was unexpected was the discovery that it remained so geologically active. Pluto was observed to be a strange world full of water ice mountains with fresh glaciers of frozen Nitrogen.

Already considered to be an outstanding success, the New Horizons spacecraft has since been continuing on its journey at a speed of around 32,000 mph (around 9 miles per second). At this speed, it has now reached a point more than a billion miles further away than Pluto, about four billion miles from Earth in total. Meanwhile, NASA have been busy adjusting its path in order to direct it toward a new target. This time, it’s a smaller object called Ultima Thule (pronounced Toolee), part of the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt is a vast area of small rocky debris which surrounds the solar system outside the orbits of all the major planets. It’s a bit like the Asteroid Belt, only much further away.

Ultima Thule is the most distant object ever to be visited by a spacecraft. In fact, it wasn’t even discovered when New Horizons was launched in 2006. But in the very early hours of January 1st, it achieved its goal, performing a variety of observations during its fly-by. At closest approach, it was about 2,200 miles away from the object.

This really is a stunning achievement. The spacecraft is flying incredibly fast, with very poor light, as it is so far from the Sun. In fact, it is so far away that a radio signal (which travels at the speed of light) takes around six hours to reach the spacecraft from Earth. Managing to take a photograph of such a small object, when it is so dark and distant, is a feat of spectacular proportions. It is remarkable to be able to get any kind of image at all.

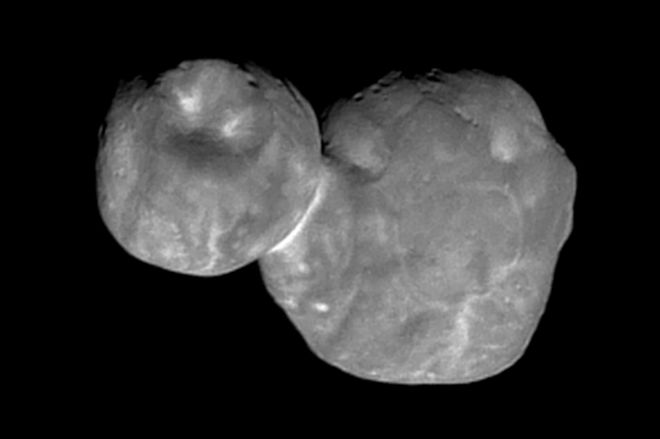

With data transfer speeds of around 1kb per second, it would make old school dial up internet connections seem fast. It will therefore take nearly two years to get all the data back, but the first fuzzy photograph shows an object shaped like a snowman. The resolution of this first image is not sharp – it has a resolution of about 150 yards per pixel. But this is more than enough to be able to distinguish two spherical shapes, which form a large “body”, attached to a smaller “head”. It is around twenty miles long in total. Better resolutions will be achieved as further data is transmitted over the coming months.

The reason why this is important is that by discovering more about this ancient object, we hope to find out more about how the solar system was created. This is because the debris within the Kuiper Belt is thought to be made up of the remnants from when the planets first formed – a kind of left over rubble. Being so far away from the Sun’s light and at temperatures approaching absolute zero, this space debris is thought to be largely unchanged from the very dawn of the solar system, some 4½ billion years ago.

China successfully lands its Chang’e 4 spacecraft on the far side of the Moon

This momentous feat was achieved on January 3rd. Named after the Chinese Moon goddess, Chang’e 4 represents the very first successful soft landing of a spacecraft on the far side of the Moon.

This may not seem like a major breakthrough at first sight – many spacecraft, including a dozen humans have been to the Moon before after all. But the far side of the Moon is a very difficult challenge. Firstly, here on Earth, we can never see it. As a result of billions of years of the Earth’s gravitational influence, the Moon now rotates on its axis at exactly the same rate as it orbits the Earth. This is known as a “tidal lock”. This means that we always see the same half of the Moon’s surface facing toward us. It also means that a lunar day is the same length as a lunar year (around 28 Earth days).

This leads on to the second major problem. Just as we cannot see the far side of the Moon, we cannot send or receive any radio signals directly to or from it either. The Apollo astronauts experienced a radio black out when they were orbiting “behind” the Moon for this reason. Any spacecraft that lands on the far side of the Moon is therefore unable to communicate directly with us on the Earth.

Thirdly, the far side of the Moon also has a more uneven, boulder strewn surface than the side we are more familiar with. This is because the visible side is protected from being hit by meteorites, comets and other space bound rocks and debris by its larger partner, the Earth. The far side is more open to this constant bombardment over the billions of years of its history, so it is more cratered and uneven.

The Chinese mission solved the first two of these problems with an ingenious solution. In May 2018, a satellite called Queqiao was launched into an unusual orbit called a “halo” orbit. This is a specific point in space where the spaceship is able to orbit both the Earth and the Moon while maintaining a stable position relative to both bodies. This is known as a Lagrangian Point. The satellite is effectively “parked” in space, with a clear line of sight (and therefore radio signal) to both the Earth and the far side of the Moon. This satellite is then able to act as a radio signal relay station, enabling Chang’e 4 to bounce its data from the surface of the Moon back to mission control on Earth via the orbiting satellite. The remaining issue of the dangerously uneven surface needed to be resolved by finding a suitable smooth surface to land on…

The robotic lunar lander Chang’e 4 was launched in December 2018. It contained an additional spacecraft, a small rover vehicle called Yutu 2. This dual craft was sent into lunar orbit, where it remained for around three weeks while further adjustments were made to its orbit and software, and a suitable landing site could be found.

The lander finally touched down in the early hours of the morning (UK time) on January 3rd 2019. It achieved this using its own on board technology, without any direction from its Earth bound operators at mission control. Its final destination was the Aitken Basin, a smooth crater not far from the lunar South Pole. The first photographs were relayed back to Earth very shortly after this, confirming the successful landing to the world. The on board lunar rover Yutu 2 was deployed about 12 hours later.

The pair of landers are expected to carry out a number of observations and experiments. These include a study of the composition of the surface of the crater, thought to have been formed by a massive impact several billion years ago. Further tests will investigate whether the far side of the Moon is a suitable place to carry out radio astronomy. This is because it will be shielded from radio signals from Earth, which pollutes earth bound observations with additional “noise”. There is also a panoramic camera, a radar probe and a mineral spectrometer.

Perhaps the most spectacular experiment of all will be an attempt to grow some seeds and flowers on the surface of the Moon. A sealed container is being used for this purpose, containing nutrients, air and water. The toughest challenge will be to maintain a suitable temperature, bearing in mind that conditions on the lunar surface can vary from around -170°C to over 100°C, boiling point on Earth. This will be yet another ground breaking achievement if successful, providing useful information for any proposed future human colonists.